Close your eyes and picture a bird, with a bone in its beak.

Any bird, any bone, any beak.

It is most likely that, when you do this, an image appears inside your mind’s eye. It is most likely that you have a mind’s eye. It’s possible that the bird in your mind’s eye, despite the bone in its beak, might sing for you. That you might hear its song in your mind’s ear.

Like somewhere between two and four percent of folks, I do not have a mind’s eye (or ear, or tongue). The technical term for this lack of a visual imagination—for image-free thinking—is aphantasia. Dr Adam Zeman coined the term congenital aphantasia to refer to folks, like me, whose imagination is blind.

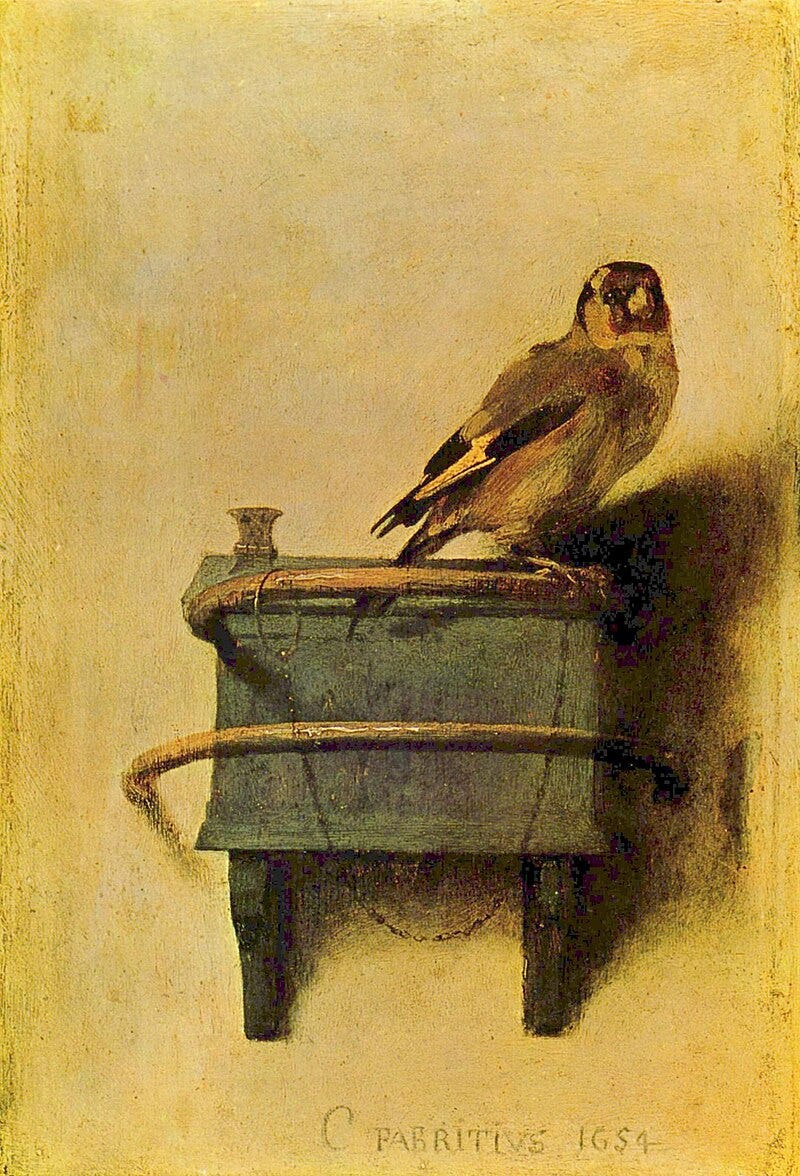

When I close my eyes I see a blank, mostly black screen. Sometimes little phosphenes floating like errant stars. When I try to picture a bird with a bone in its beak, I think about birds, and bones, and beaks. I recall images I have seen of birds. Today, the image that I remember is Carel Fabritius’s ‘The goldfinch’ (1654), made newly famous by its central role in Donna Tartt’s novel The goldfinch (2013).

I think of the texture of the paint, the way it curves around the bird’s shoulders, head, and breast. Like tiny gold waves breaking against a shoreline.

I think of Carel Fabritius, a student of Rembrandt, who died in October, 1654, just 32 years old, during the Delft Thunderclap (the explosion of about 30 tonnes of gunpowder, stored in a former convent, which killed over one hundred people). Carel was crushed beneath the rubble for fifteen hours before, according to an account by Arnold Houbraken, ‘the soul that had lingered in his body moved out’.

‘The goldfinch’, which Fabritius painted during the year of his death, is one of only twelve surviving works made by the artist. Most were destroyed by the same Thunderclap that destroyed their creator.

Picture one of those missing works. Another bird, perhaps. Another bird with a bone.

I think of bones, broken. Of the bones in my left foot, broken when I was a child and never properly healed. I remember the pain and the swelling and the mottled bruises. I think of my childhood. I think of how my sisters and I would compete over the breastbone of a devoured chicken. How two of us would we curve our pinkies around a rib each and pull until the bone snapped, to see who would get the lucky furcula where the two clavicles fuse.

While Zeman was the first modern scientist to study aphantasia, he was not the first to describe the phenomenon.

In 1880, Francis Galton published a paper in the journal, Mind, titled ‘Statistics of mental imagery’. It is sometimes referred to by the more informal and quite appealing name: the breakfast study. Galton surveyed around 100 adult English men, and 172 ‘Charterhouse boys’ (students of WH Poole, the Science Master of Charterhouse). He asked all of these participants to ‘think of some definite object—suppose it is your breakfast-table as you sat down to it this morning—and consider carefully the picture that rises before your mind's eye’ and then he asked them to reflect on the clarity and specificity of the images their minds’ generated. In particular, he asked them:

1. Illumination.—Is the image dim or fairly clear? Is its brightness comparable to that of the actual scene ?

2. Definition.—Are all the objects pretty well defined at the same time, or is the place of sharpest definition at any one moment more contracted than it is in a real scene?

3. Colouring.—Are the colours of the china, of the toast, bread-crust, mustard, meat, parsley, or whatever may have been on the table, quite distinct and natural?

Several of the men and boys reported that they could not visualise their morning’s breakfast. My favourite aphantasic adult man reports:

Dim and indistinct, yet I can give an account of this morning's breakfast table;—split herrings, broiled chickens, bacon, rolls, rather light coloured marmalade, faint green plates with stiff pink flowers, the girls' dresses, &c., &c. I can also tell where all the dishes were, and where the people sat (I was on a visit). But my imagination is seldom pictorial except between sleeping and waking, when I sometimes see rather vivid forms.

And here we are again with birds and bones.

A late Victorian gentleman (Galton described the adult men he studied as ‘persons of distinction in various kinds of intellectual work’) at his breakfast. A chicken’s wishbone grasped between one of his hooked fingers and that of a girl in a dress, perhaps as stiff with pink flowers as those green plates. The bone will not snap, since the chicken has been broiled, but splits softly along a seam. And the little girl—let us call her Anne—emerges triumphant. Tucks the lucky furcula into her pocket.

Later in the day, when she is lying in the unmown grass, watching clouds drift across a Victorian English sky, she will take it out and make a wish. She will close her eyes and imagine something wondrous, something beautiful and strange, something only her blind imagination can perceive.

This newsletter is still evolving. For now, the idea is to publish familiar essays across a broad range of themes: life, love, writing, reading, the natural world, folklore and fairy tales, and other catastrophes.

If you have constructive feedback to offer, particularly in terms of things you’d like me to write about, or write more about, please let me know by posting in the comments. Also, if you have questions you’d like me to explore or even attempt—in my ever-ambling way—to answer, I’d love to hear them.

Thank you for reading!

Love this!