It’s been a minute since I last posted. I had all the best intentions in the world, but illness and other distractions got the better of me. I’ve also been secretly working on a post about third person, and head hopping, that’s taken me down the rabbit hole. It’s coming! (Next week, I promise/hope).

In the meantime, I’ve had the great joy of having several wonderfully bracing conversations over the last fortnight, filled with laughter, earnestness, courage, and warmth. One feature of these conversations was a series of philosophical questions that arose, and I thought I’d share these (the questions, not the long, unweildy, crazy conversations they provoked!), and ask you what you think.

There are three: feel free to respond to none, one, or all of them, and in as much as or little detail as you like.

#1 The end of the world as we know it

First up is a kind of worldbuilding question—doodling with the future—that arose out of a conversation about the impact AI will have on our lives. Here is the basic premise of our ‘future’ world:

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) has advanced to the extent that it can do any intellectual work a human can do, but faster and with greater accuracy. This has resulted in massive and widespread unemployment, and a resulting worldwide economic collapse. Capitalism is dead.

In response to the collapse of the economy, and the redundancy of most forms of work as we currently understand it, the government introduces four interlinked reforms:

A UBI (Universal Basic Income) that provides enough income for everyone to meet their basic needs for housing, food, clothing, etc.

Healthcare and education are universalised as well. That is, healthcare and education (primary, secondary, and tertiary) are free, and accessible to everyone.

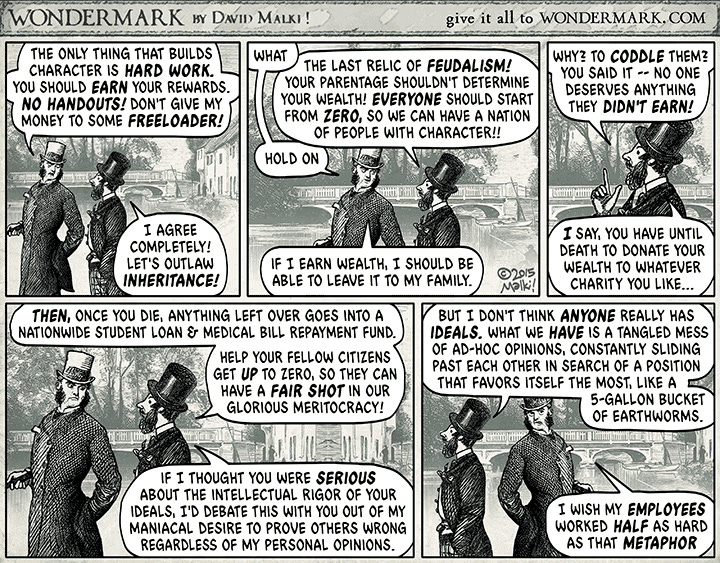

In order to fund some of this, and address historical inequities resulting from wealth hoarding, inheritance has been outlawed. That is, when you die, any assets you hold go into a fund that provides the UBI, universal healthcare, and universal education. (An idea inspired by the issue of David Malki’s Wondermark, below).

The conversational invitation: What would life look like in such a society/future, for you or people like you? What would people do with their lives now that work is, perhaps/essentially, optional? Would people work, and if so, what would they do for work? Why would people work (what would motivate them)? What impact would it have on people’s lives to have all of their basic needs met? Is this a utopian, or a dystopia? Or, to put it a different way, who would experience such a world as a utopia, and who would experience it as a dystopia?

#2 Crime and punishment

Our second philosophical conversation-starter revolves around criminal justice. Here goes:

If the criminal justice system was set up such that, if a person is convicted of a crime, and that crime involved harming you or your loved ones, punishment was provided purely by retribution. That is, sentencing is based on a very literal interpretation of reciprocal justice, as expressed in Exodus 21:23–27:

23 But if there is serious injury, you are to take life for life, 24 eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, 25 burn for burn, wound for wound, bruise for bruise.

The kicker is that you—the person who was harmed by the criminal, or their nearest surviving relative if the crime was murder or manslaughter—must carry out the punishment yourself. You could not merely give permission for an executioner to do the deed, and you could not do the deed using a humane (?) substitute method, such as death by lethal injection.

The conversational invitation: If someone murdered someone you loved (your spouse/sibling/parent/child), would you—could you—kill the convicted perpetrator? Consider other forms of interpersonal crime—crimes where a person is injured or harmed in some way (bodily, emotionally, financially)—what sorts of crimes would you be comfortable performing retributive justice for? What sort of crimes would you not want to punish in this way (for me, one form of crime I think nobody would want to punish using personally-performed retributive justice is sexual assault)?

Would such a criminal justice system be more, or less, effective than our current one/s for preventing crime, or criminal recidivism (repeat offending)?

How would such a system respond to crimes without a direct or explicit victim, such as drug use, or even drug distribution?

Utopia? Dystopia? A bit of both?

What would a justice system based on restorative justice look like? (Or on some other form of justice: procedural, or distributive?)

What does justice mean to you? Is it important? Does it require that people suffer/be punished for their wrongdoings? Does it require that those who have suffered or been harmed are offered …. compensation? Retribution? Some other form of redress or repair? In this thought experiment, enacting justice includes doing harm: how is the harm performed as punishment just?

What other questions/considerations does this thought experiment raise for you?

Have you thought about it’s almost polar opposite model: abolishing or dismantling the prison-industrial complex. Getting rid of police, courts, and prisons/gaols.

This particular thought experiment reminds me of the classic thought experiment ‘Heinz dilemma’, so out third and final conversation starter is that old one …

#3 Heinz dilemma

The Heinz dilemma is a moral question/conundrum often used in teaching morality, ethics, or psychology. The following version of it comes from psychology, and in particular from Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory regarding the six stages of moral development (a theory or model that was derived from Jean Piaget’s work on life stages). Kohlberg believed that moral development was a life-long process, based on a constantly-evolving understanding or interpretation of justice.

Importantly, in identifying the stages of moral development—including the stage an individual might be at—Kohlberg was more interested in the rationale one gave for their answer to the conundrum, than the answer itself. So the most important question in Kohlberg’s version below is Why, or why not?

A woman was on her deathbed. There was one drug that the doctors said would save her. It was a form of radium that a druggist in the same town had recently discovered. The drug was expensive to make, but the druggist was charging ten times what the drug cost him to produce. He paid $200 for the radium and charged $2,000 for a small dose of the drug. The sick woman's husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about $1,000 which is half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said: ‘No, I discovered the drug and I'm going to make money from it.’ So Heinz got desperate and broke into the man's laboratory to steal the drug for his wife. Should Heinz have broken into the laboratory to steal the drug for his wife? Why or why not?

The conversational invitation: Obviously, the first place to start is with Kohlberg’s questions: Should Heinz have broken into the laboratory to steal the drug for his wife? Why or why not?

But you might also like to consider other questions, such as: Is the druggist justified in withholding the drug from Heinz? Is it, more generally, ok for medical experts and/or practitioners to withold care from those who need it? Who else is, or should be, responsible for ensuring that Heinz’s wife gets the medical care she needs? How do we (you) negotiate between the rights of inventors, creators, manufacturers, distributors, etc, and the rights of those who ‘need’ what they are creating/selling?

Would it make a difference to your answers if Heinz’s wife’s illness was not life threatening? What if the drug she needed was not urgent or (strictly speaking) necessary for her survival? What if it was anti-depressants or anxiety medication? Puberty blockers or HRT (Hormone Replacement Therapy)?

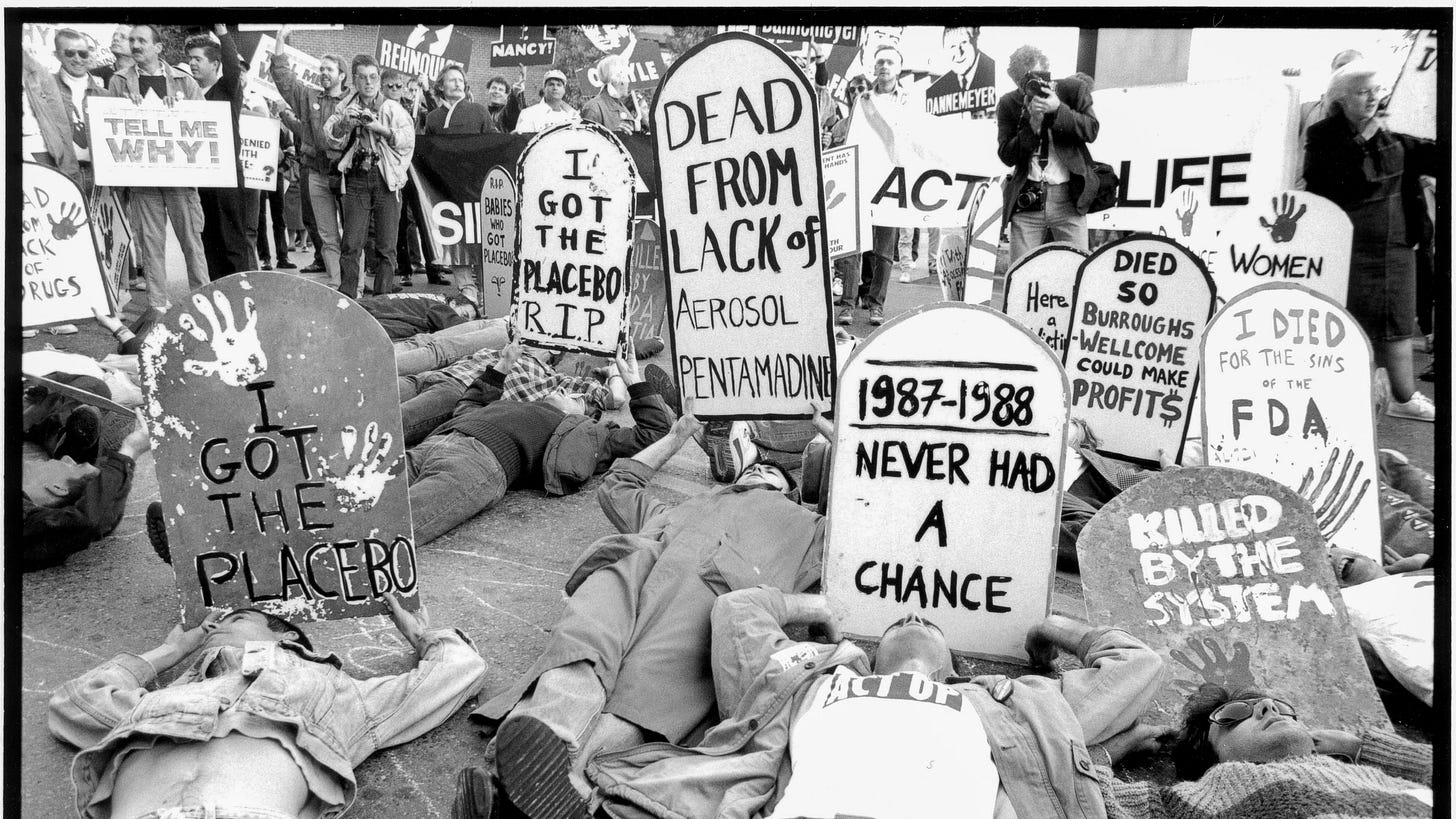

What impact does it have on the scenario that the healthy (straight, presumably white and able-bodied) husband is the active focus of the narrative, rather than his (also presumably white and straight) wife? Would it make a difference if the roles were reversed (dying husband, thieving wife)? Or if you recast the relationship in other ways (Dying parent/thieving child? Dying patient/thieving caregiver?) Did you picture everyone in the scenario as white, straight and middle-class (ie: as inhabiting the ‘unmarked state’1)? The image above shows a demonstration protesting the inaccessible cost of drugs that would (at the time) have saved the lives of AIDS sufferers: would these sufferers and their loved ones have been justified in breaking the law in order to acquire life-saving medical care? Why, or why not? That is, in what ways does your sense of what’s morally appropriate shift when it’s not one straight woman whose life is held in the balance, but thousands of people, mostly queer men.

Ok, that’s three juicy conversation starters/ethical dilemmas for us to chew on! I can’t wait to read your responses and engage, with you, in unpacking why we think and feel the way we do.

This newsletter is still evolving. For now, my intention is to publish familiar essays across a broad range of themes: life, love, writing, reading, the natural world, folklore and fairy tales, and other catastrophes. If you can afford to do so, I would be enormously grateful if you sponsored my writing by taking up a paid subscription.

If you have constructive feedback to offer, particularly in terms of things you’d like me to write about, or write more about, please let me know by posting in the comments. Also, if you have questions you’d like me to explore or even attempt—in my ever-ambling way—to answer, I’d love to hear them.

Thank you for reading!

The concept of ‘markedness’ was first introduced by linguistics researchers, Nicolas Trubetzkoy and Roman Jakobson. Markedness is somewhat similar to the concept of ‘Otherness’: it is the state of standing out as nontypical, as opposed to regular or common. In a marked–unmarked relationship, one term of a binary pair is the broader, dominant one, and is often understood as normal or assumed. In literary and other texts (like Kohlberg’s), most characters are initially understood as inhabiting an ‘unmarked state’. That is, they are assumed to be ‘normal’ or ‘common’, until they are explicitly marked as divergent or unusual.

Markedness/unmarkedness is, at its core, a simple idea: there’s stuff that the reader considers ‘normal’ that they will drag into the story to fill in any and all gaps or silences in the text. For example, unless you explicitly state, or very strongly imply, that a character is black or gay, the reader will assume that they are not: that is, that they are white, and straight. Importantly, what a reader considers ‘normal’ in a character doesn’t have to, and often doesn’t, reflect their own identity. I’m queer, but I usually assume that characters are straight until they do or say something that suggests otherwise.

The unmarked state of most characters in contemporary fiction, and texts like Kohlberg’s—nonfiction, including educational texts—is exactly what you’d expect: white, able-bodied, middle-class, etc.

In Kohlberg’s narrative, the three characters are marked in very mininal ways: we know that Heinz is male, and perhaps (because of the Germanic name) we think of him as German or Germanic; we know the druggist is a druggist, and male; we know that the wife is sick, dying from some unspecified disease. Most readers fill in the blanks by unconscious reference to the unmarked state: that is, by assuming—until we are told otherwise—that the characters are white, straight, middle-class, able-bodied (except the wife), etc.

Oh! I knew there was one more! My dear friend Tara asked us, over coffee, whether we'd choose to have a glimpse of the future, or an opportunity to change one thing about our past. Which would you choose, and why?